Questions about the original creator of the Tarot deck, the time and place of its creation, the significance of its complex symbolism, and even the origin of the name Tarot, have long been the subject of wild speculation. Most historians today believe that Tarot cards first appeared in northern Italy around the beginning of the 15th century. They also suggest that the Tarot has undergone significant changes before stabilizing into the form we know today.

The two parts of the deck probably come from different sources. The minor suits are believed to have originated from playing cards, first used in China. These were later propagated in India, before reaching Italy through the Islamic countries in the late middle ages. Indeed, China and India have old games of cards with suits consisting of aces, numbered cards and court cards. Muslim playing cards from the Mamluk period even show suit symbols which are visually very similar to the four Tarot suit symbols.

The major suit, on the other hand, appears to be a European invention. There is nothing similar to it in Asian countries, and its imagery clearly points to late European medieval or early renaissance influences. Historical records do not provide us with any hint as to why it was created or how it became united with the four-suit playing cards coming from the East. What we do know is that from the 15th century onwards the combined Tarot deck, consisting of both the major and the minor cards, was widely used for playing games of chance in both aristocratic and popular circles.

It is also unclear as to why the combined deck has become known as the Tarot. Several hypotheses exist. My favorite one links the name “Tarot” to the word taroccho, which in common 16th century Italian meant “fool, a dumb person”. This could, of course, be understood negatively as suggesting that only fools spend their time and money on card games such as Tarot. But we can also think of other interpretations. In the major suit there is one card called “the Fool”. It is often considered special and has a unique status in the suit, as we shall later see. The original meaning of the name “Tarot cards” may thus have been “the Fool’s cards”, referring to this particular card or to the figure appearing on it.

Over the next few centuries the use of the Tarot deck spread throughout different parts of Italy, followed by its migration to countries such as France, Germany and Switzerland. There is some fragmentary evidence of the use of Tarot cards in popular fortunetelling and possibly sorcery. However, these seem to be isolated cases rather than a widespread practice. During that time, Tarot cards were mostly used for gaming. But the combination of the two parts of the deck proved to be too complex for card games. Eventually, card players preferred the simpler pattern of only four suits with aces, numbers and court cards. These became the ordinary playing cards which are used today all over the world. The complete Tarot deck continued to exist, but after the 18th century it was used mainly by fortunetellers and mystics. In various parts of Europe one can still find traditional card games with a 78-card deck resembling the Tarot, but this is only a marginal practice today.

Academic historians who have studied the Tarot tend to believe that this is the whole story. In their view, people at that time used the cards for the sole purpose of gaming without paying much attention to the symbolism of the images. However, even without having solid proof that something is missing from this story, it is difficult to understand the role of the major suit in it. If people in Italy merely wanted to adopt an oriental card game, why would they make it more complicated by adding 22 cards of such different character? Indeed, card-players in Europe would later discover that it was more convenient to do without them.

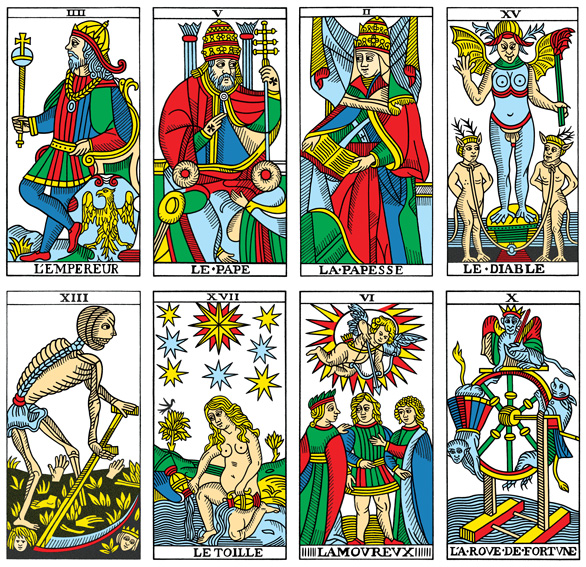

The question seems even more puzzling when we consider the imagery of the major suit cards. Two cards bear images of the Emperor and the Pope. These were traditional figures of political and religious authority at that time. But other cards present strange themes and figures such as a woman Pope, a bisexual devil, a skeleton with a scythe, demons and angels and a host of naked figures. All these appear to be on the same level as the figures of authority and social order. One card called The Wheel of Fortune even shows an image which traditionally represents revolutions and the casting down of rulers. At a time when any disrespect towards the king or the church was severely punishable, propagating this collection of unruly images seemed like asking for trouble.

Another point to remember is the fact that the images on the cards have no significance in gaming. The usual rules of card games refer only to the rank and value of each card, rather than the details of its illustration. The same cards could therefore be played in exactly the same way even if their images had been replaced, for example, by a simpler design consisting only of numbers and titles with some innocent decorations. Yet for nearly four centuries, Tarot card makers preserved the original set of images. They did express their creativity by modifying certain details, but the general structure and the card themes have remained almost intact.

Why did they do it? Why did the Tarot card makers insist on preserving a set of images loaded with such heavy and dangerous symbolism, if it was irrelevant to the gaming needs of their clients? And how did it at all happen that a modest deck of playing cards picked up a set of symbols rich and potent enough to inspire centuries of varied interpretations, speculations and activities, as the later history of the Tarot shows?

Various answers have been offered for these questions. As we shall see later on, many authors who attributed mystical meanings to the cards believed that the Tarot was created by ancient sages, who wanted to express a secret spiritual message under the guise of seemingly innocuous playing cards. According to these authors, the secret of these playing cards was passed among Tarot card makers for many generations. This unwritten tradition explained the true meaning of each card, and instructed the card makers to preserve the original illustrations. In other words, the Tarot makers were a sort of conspirational guild, manipulating European card players into spreading the ancient message without being aware of its real significance.

Still, as a historical theory, this idea is very problematic. It is difficult to explain how such a secret could have been preserved through centuries of wars and social upheavals without ever being revealed. It is also unclear why, after four centuries of continuous transmission, the ancient tradition suddenly vanished without a trace just as interest in the significance of Tarot cards became widespread. No traditional card maker has said anything about this since the beginning of the 19th century.

And what if there was no such secret tradition? If we accept this possibility, then it must have been something in the images themselves that influenced people’s minds for centuries, motivating them to preserve this ancient set of symbols. Thinking further along these lines, we may note that many authors propagating the “secret society” theory give the impression of a highly disciplined group of initiated sages with a strong spiritual motivation. However, it is more reasonable to think that as a game of chance, the cards actually existed in borderline social areas such as in clubs of gambling, drinking and cheap pleasures. Tarot making itself seems to have been a shady occupation. In fact, many historical accounts are concerned with pirated, forged and contraband card decks. Thus, it may be more reasonable to think of the Tarot cards as a collective artwork evolving in marginal and half-legitimate popular circles, rather than as sublime teaching kept in secret temples of wisdom and spirituality.

What, then, was the role of these complex symbols, imbued with such strong spiritual and emotional meanings, in the questionable gambling venues? One possibility is to look for a psychological answer. Maybe the card images were somehow reflecting the subconscious conflicts and dilemmas of the card players. Maybe, in the very places where state authority (The Emperor) and the church (The Pope) lost their convincing power, people needed some reminder of the complex interplay between light and darkness in human life. We should remember, of course, that people at the time were very religious, so the thought of doing something forbidden must have evoked their deepest conflicts and fears. Maybe contemplating the complex symbols somehow helped them maintain a moral balance while also flirting with the dark, tempting world of sin. Such an idea might explain why they did not want the illustrations to be replaced by less charged images.

Yet, something in the elusive and mysterious character of the Tarot may inspire us to go beyond purely psychological explanations. We can at least play with the idea that there is something more to it. Maybe the magic of the cards represents some real magic in the world. Maybe there is a meaningful pattern originating in another level of reality, which the Tarot cards channel and express at the human level.

The term “channeling” is usually associated with a message from a higher level of reality transmitted to our world through the mind of a single person. Yet the Tarot cards may represent another kind of channeling. Not a single message transmitted through a single person, but rather a web of small messages planted in the subconscious minds of many people at different times and places. One can think of it as collective channeling, with each person experiencing the message as a tiny impulse or an intuitive urge. One person may feel a desire to print a set of cards preserving the old symbols. Another might have the urge to improve it by modifying this or that detail. Others may have an intuitive preference for a specific version of the cards, and so on. The impulse can be small and almost imperceptible on the level of a single individual. Sometimes it brings about real action, while in other cases it remains as an obscure and unfulfilled urge. It is the collective impact of all these little pushes that finally gives rise to the big-scale evolution of Tarot cards in human history.